Today, I woke up to some good news. Two more of my poems were today’s offerings on the Substack site Second Coming, a poem-a-day protest against the threats to our democracy by our current administration.

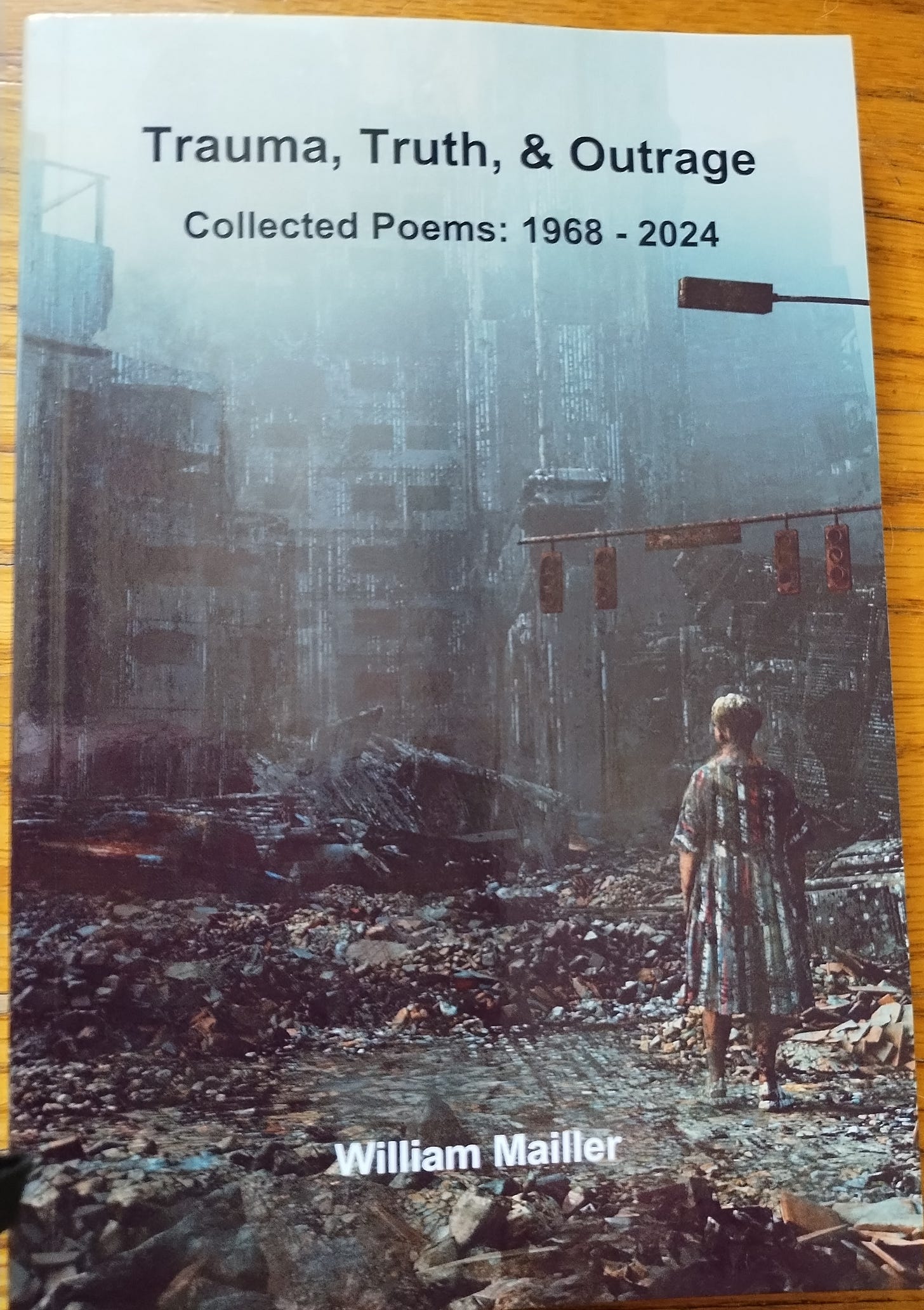

And last night, I went to hear a writing colleague, Bill Mailler read from his new book of social justice poetry, Trauma, Truth, and Outrage. Bill’s poems tend to be gut-punches. He doesn’t shy away from horror or attempt to beautify it through language. His work is like that sign our small group of witnesses illuminated at the border in 2020: Don’t Look Away.

What I liked most about Bill’s work were the questions relating to our human capacity for meanness, a key component of the poem, Meditations on My Whiteness, where he asks directly:

For what possible reason

could good or well-meaning people perpetuate or participate….before offering a long lamentation of possibilities including:

because we are cowards and cannot acknowledge the consequences of our actions?

because we teach our children to deny their natural empathy for others, themselves, animals, and the earth itself?

I also think constantly about the issue of human cruelty. Though my own work tends to take a less direct approach to writing about political issues, neither is wrong or right. They’re just different. The point, I think, is to enter the world through a lens of empathy, rather than simply ranting or trying to be prescriptive about what you think should be done. Poet Kwame Dawes talks eloquently about this issue in his own writing: When I write the poems about Haiti, people living with the disease, I’m not writing poems so that people will give.. but so the person who experiences when they read the poem, they’ll say to me… that’s it. That’s what I’ve been feeling but I didn’t know how to say it.

As many of us are staggering through these times with deep and heavy feelings about what’s happening in the world, reading a protest poem or a political piece of artful prose can help us feel less isolated as we try to make sense of our grief and uncover a path through it into some kind of meaningful action. That’s why when I’ve read my own protest poems at workshops or readings, even raw and unfinished generative responses to prompts, I often got more positive feedback than I expected because I was able to verbalize something that someone else had not yet been able to verbalize–touched a nerve, so to speak.

This isn’t to say writing protest poetry is easy. While I do believe that all attempts at creative expression should be acknowledged, respected, and validated, it’s difficult not to fall into ranting, generic abstractions, slogans, self-pitying, etc. And the problems with these pitfalls is that it becomes easier to lose the reader, who’s likely heard it all before and can gloss over or check out. Keeping empathy in the forefront can help. So can paying careful attention to language–using sensory details, fresh verbs, and unexpected metaphors. In prose, this might mean creating vivid scenes where the viewer can watch what’s happening to characters and form their own judgments.

What has made the process of writing protest poems and stories slightly easier for me in the past decade has been my being able to more fully integrate my life as a writer and an activist. While this wasn’t true in my earlier life, I now feel the fallout from political issues as viscerally as the other subjects I feel urged to write about. Allowing myself to deeply feel the horrors of all I read about in the news has certainly made it more difficult to maintain emotional balance, but I do think it’s necessary. We need, somehow, to find a path into a more deeply rooted empathy if we really want to break the pattern of ignoring atrocities–often done in our name by a system in which we are all still passively participating.

Well said.

Congratulations on this good news, Dina that is so we'll deserved.